Zusammenfassung

Angesichts der raschen Ausbreitung des Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), das ein schweres akutes respiratorisches Syndrom verursacht und zur Coronavirus-Krankheit 2019 (COVID-19) führt, haben Unternehmen, Bundes-, Landes-, Kreis- und Stadtverwaltungen, Universitäten, Schulbezirke, Gotteshäuser, Gefängnisse, Gesundheitseinrichtungen, Organisationen für betreutes Wohnen, Kindertagesstätten, Hausbesitzer und andere Gebäudeeigentümer bzw. -nutzer nun die Gelegenheit, das Übertragungspotenzial durch Maßnahmen im Rahmen eines Built-Environment-Konzeptes (BE, „gebaute Umwelt“) zu reduzieren. In den vergangenen zehn Jahren wurden umfangreiche Forschungsarbeiten über das Vorhandensein, die Häufigkeit, die Vielfalt, die Funktion und die Übertragung von Mikroben in der gebauten Umwelt durchgeführt und häufige Wege und Mechanismen der Erregerweitergabe aufgedeckt. In diesem Papier fassen wir diese Mikrobiologie der BE-Forschung und die bekannten Informationen über SARS-CoV-2 zusammen, um Entscheidungsträgern im BE-Bereich, Gebäudebetreibern und allen Bewohnern von Innenräumen eine praktikable und realistische Anleitung zu geben, wie sie die Verbreitung von Infektionskrankheiten durch umweltbedingte Übertragungswege minimieren können. Wir glauben, dass diese Informationen den Unternehmen, öffentlichen Verwaltungen und Privatpersonen, die für bauliche Maßnahmen und Umweltleistungen verantwortlich sind, die Entscheidungen bezüglich des Ausmaßes und der Dauer sozialdistanzierender Maßnahmen während viraler Epidemien und Pandemien erleichtern können.

Autor-Video: Es ist eine Autor-Videozusammenfassung dieses Artikels verfügbar.

Einführung

Aufgrund der weltweit zunehmenden Infektionen mit SARS-CoV-2, das die Coronavirus-Krankheit 2019 (COVID-19) verursacht, werden die Prävention und Bekämpfung von SAR-CoV-2 sowohl in der wissenschaftlichen Gemeinschaft als auch in der breiten Öffentlichkeit mit Interesse und Besorgnis verfolgt. Viele der aktuell umgesetzten Maßnahmen gehören zum Standard-Repertoire der Eindämmung virologischer Atemwegserkrankungen, doch es sollten auch andere, weniger bekannte Übertragungswege in den Blick genommen werden, um eine weitere Ausbreitung zu verhindern. Beispielsweise sind durch die Umgebung begünstigte Übertragungswege in Gebäuden bei anderen Krankheitserregern seit Jahrzehnten ein Problem, vor allem in Krankenhäusern. In den vergangenen Jahren wurden umfangreiche Forschungen über das Vorhandensein, die Verbreitung, die Vielfalt, die Funktion und die Übertragung von Mikroorganismen in der gebauten Umwelt (BE) durchgeführt. Dank dieser Arbeit konnten häufige Wege und Mechanismen der Keimverbreitung identifiziert werden, die Rückschlüsse auf mögliche Verfahren zur Eindämmung von SARS-CoV-2 durch Maßnahmen im BE-Bereich zulassen.

Coronaviren (CoVs) verursachen meist nur milde Symptome, doch sie haben in den vergangenen Jahren gelegentlich auch zu schwereren Krankheitswellen geführt. Wenn es zu einem Überspringen von einem tierischen auf einen menschlichen Wirt (1) (zoonotische Übertragung) kommt, so liegt dies meist an Mutationen, die strukturelle Veränderungen im Coronavirus-Spike-(S)-Glykoprotein verursachen und so die Bindung an neue Rezeptortypen ermöglichen – dies kann das Risiko großer Ausbrüche oder Epidemien erhöhen (2). Im Jahr 2002 wurde in der Provinz Guangdong in China ein neues CoV entdeckt, das Severe Acute Respiratory Virus (SARS) (3). SARS ist ein zoonotisches Coronavirus, das ursprünglich aus Fledermäusen stammt und beim Menschen zu Symptomen wie anhaltendem Fieber, Schüttelfrost/Rigor, Myalgie, Unwohlsein, trockenem Husten, Kopfschmerzen und Atemnot führt (4). Bei SARS betrug die Sterblichkeitsrate 10 %, in den Jahren 2002 bis 2003 infizierten sich während eines 8-monatigen Ausbruchs 8000 Menschen mit diesem Erreger (5). Etwa zehn Jahre nach SARS tauchte ein weiteres neuartiges, hoch pathogenes Coronavirus auf, das als Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) bekannt ist und das vermutlich ebenfalls aus Fledermäusen stammt, wobei Kamele als Zwischenwirte dienen (6). Das MERS-Coronavirus wurde zuerst auf der Arabischen Halbinsel beschrieben. Es breitete sich auf 27 Länder aus, mit einer Sterblichkeitsrate von 35,6 % unter 2220 Erkrankten (7).

Die Coronavirus-Krankheit 2019 (COVID-19)

Im Dezember 2019 wurde das neuartige Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in der Stadt Wuhan in der Provinz Hubei, einem wichtigen Verkehrsknotenpunkt in Zentralchina, entdeckt. Die ersten COVID-19-Fälle wurden mit einem großen Markt für Meeresfrüchte in Wuhan in Verbindung gebracht, was zunächst auf einen direkten Übertragungsweg über Nahrungsmittel hindeutete (8). Seither hat man herausgefunden, dass die Übertragung von Mensch zu Mensch einer der Hauptwege bei der Verbreitung von COVID-19 ist (9). Nachdem die ersten Fälle erkannt wurden, hat sich COVID-19 innerhalb weniger Monate auf 171 Länder und Territorien ausgebreitet, und es gibt etwa 215 546 bestätigte Fälle (Stand: 18. März 2020). Es wurden die Übertragungswege Wirt-zu-Mensch und Mensch-zu-Mensch identifiziert. Es gibt vorläufige Hinweise darauf, dass eine umgebungsvermittelte Übertragung möglich sein könnte – dies bedeutet, dass COVID-19-Patienten möglicherweise durch das Berühren einer unbelebten Oberfläche in einer gebauten Umgebung infiziert wurden (10, 11).

Die Epidemiologie des SARS-CoV-2

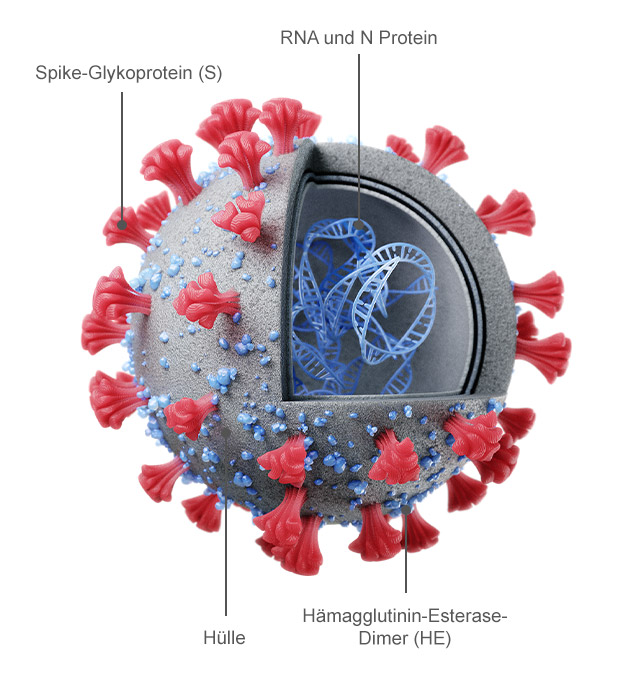

Das Betacoronavirus SARS-CoV-2 ist ein behülltes Einzelstrang-RNA-Virus mit positiver Polarität, dessen Genom eine Länge von ca. 30 kb hat (12, 13). Die keulenartigen Fortsätze, die aus seiner Zelloberfläche herausragen, sind Spike-Glykoproteine; sie können sich anheften und erleichtern so das Einbringen des viralen genetischen Materials in eine Wirtszelle (14, 15) (Abb. 1). Das genetische Material des Virus wird anschließend von der Wirtszelle vervielfältigt. Man geht davon aus, dass sich das Virus SARS-CoV-2 zuerst in Fledermäusen verbreitete und möglicherweise den Pangolin als Zwischenwirte nutzte (16). Es gibt mehrere andere Betacoronaviren, die in Fledermäusen als Primärreservoir vorkommen, wie SARS-CoV und MERS-CoV (17). SARS-CoV-2 manifestierte sich Ende Dezember 2019 erstmals in einer menschlichen Population: Es trat bei Personen auf, von denen bekannt war, dass sie häufig einen Markt für Meeresfrüchte besuchten (18). Die ersten klinisch beobachteten Symptome waren Fieber, Müdigkeit und trockener Husten in leichter bis schwerer Ausprägung (19). Gegenwärtig beruht das von den Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) entwickelte Diagnoseprotokoll (20) auf einer Kombination aus klinischer Beobachtung der Symptome und einem positiven Test auf das Virus, der mittels Echtzeit-PCR (rt-PCR) durchgeführt wird (21).

ABBILDUNG 1

ABBILDUNG 1Der Aufbau des SARS-CoV-2-Virus. (a) Künstlerische Darstellung der Struktur und des Querschnitts des SARS-CoV-2-Virus (14, 15). (b) Transmissionselektronen mikroskopische Aufnahme eines SARS-CoV-2-Viruspartikels, der aus einem Patienten isoliert und am NIH, genauer gesagt an der Integrated Research Facility (IRF) des National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Fort Detrick, Maryland, aufgenommen wurde (93). COVID-19 und die Rolle der gebauten Umwelt (BE) bei der Übertragung

Als „gebaute Umwelt“ bezeichnet man die Gesamtheit aller Umgebungselemente, die von Menschen errichtet oder produziert wurden, wie beispielsweise Gebäude, PKWs, Straßen, öffentliche Verkehrsmittel und andere von Menschenhand geschaffene Räume (22). Da die meisten Menschen mehr als 90 % ihres täglichen Lebens innerhalb einer gebauten Umgebung verbringen, ist es wichtig, die potentielle Übertragungsdynamik von COVID 19 innerhalb des BE-Ökosystems ebenso wie das menschliche Verhalten, die räumliche Dynamik und die Betriebsfaktoren von Gebäuden zu verstehen, da all dies die Ausbreitung und Übertragung von COVID-19 fördern oder auch eindämmen kann. Gebaute Umgebungen sind potentielle Übertragungsvektoren für die Ausbreitung von COVID-19, da sie eine enge Interaktionen zwischen Individuen herbeiführen, mikrobentragende Objekte und Flächen (Gegenstände oder Materialien, die wahrscheinlich Infektionskrankheiten übertragen können) enthalten und den Austausch bzw. die Übertragung über die Luft begünstigen (23, 24). Die Nutzerdichte in Gebäuden, die wiederum von der Art und dem Konzept der Immobilie, von deren Belegungsplan und von der Aktivität in ihrem Inneren abhängig ist, begünstigt Ansammlungen von auf Menschen übertragbaren Mikroorganismen (22). Je mehr Personen sich in den Innenräumen aufhalten und je aktiver dieser sind, desto höher ist meist die soziale Interaktion und die Übertragungsrate aufgrund des direkten Kontaktes zwischen den Individuen (25) und aufgrund des Berührens unbelebter Oberflächen in der Umgebung (z. B. mikrobentragende Objekte). Der erste Patienten-Cluster wurde im chinesischen Wuhan mit Atemnot ins Krankenhaus eingeliefert (Dezember 2019), und etwa zehn Tage später diagnostizierte dieselbe Krankenhauseinrichtung Patienten außerhalb der ursprünglichen Kohorte mit COVID-19. Es wird vermutet, dass die Zahl der infizierten Patienten aufgrund von Übertragungen, die möglicherweise innerhalb der gebauten Umgebung des Krankenhauses aufgetreten sind, angestiegen ist (10). Das erhöhte Expositionsrisiko, das mit einer hohen Personendichte und ständigem Kontakt verbunden ist, wurde anhand des COVID-19-Ausbruchs deutlich, der sich im Januar 2020 auf dem Kreuzfahrtschiff Diamond Princess ereignete (26). Die Ansteckungszahl (bekannt als R0) von SARS-CoV-2 wird aktuell auf 1,5 bis 3 geschätzt (27, 28). Der R0 Wert ist definiert als die durchschnittliche Anzahl von Personen, die von einer bereits erkrankten Person angesteckt werden (29). Zum Vergleich: Masern sind für ihren hohen R0-Wert von ca. 12 bis 18 (30) bekannt, und die Grippe (Influenza) hat einen R0-Wert von weniger als 2 (31). Innerhalb der begrenzten Räume einer gebauten Umgebung wird bei SARS-CoV-2 jedoch von einem deutlich höheren R0-Wert ausgegangen (Schätzungen zufolge zwischen 5 und 14); ∼700 der 3711 Passagiere an Bord der Diamond Princess (∼19 %) infizierten sich während ihrer zweiwöchigen Quarantäne auf dem Schiff mit COVID-19 (26, 32). Diese Zahlen verdeutlichen die hohe Übertragbarkeit von COVID-19 als Ergebnis der engen Räume innerhalb dieser gebauten Umgebung (33). Angesichts der baulichen Gegebenheiten des Kreuzfahrtschiffes spielte die Nähe der infizierten Passagiere zu anderen wahrscheinlich eine wichtige Rolle bei der Verbreitung von COVID-19 (33).

Wenn sich Personen durch die gebaute Umgebung bewegen, haben sie direkten und indirekten Kontakt mit den sie umgebenden Oberflächen. Viruspartikel können sich aufgrund natürlicher mechanischer Luftstrommuster oder Turbulenzen in der Innenraumumgebung, beispielsweise durch das Auftreten der Füße beim Gehen und Thermikblasen aufgrund der menschlichen Körperwärme, ablagern und wieder aufgewirbelt werden (22, 34). Diese resuspendierenden Viruspartikel können sich dann wieder auf den Objekten und Flächen niederlassen. Wenn eine Person mit einer Oberfläche in Kontakt kommt, findet ein Austausch von mikrobiellem Leben statt (35), d. h. es werden Viren von der Person auf die Oberfläche übertragen und umgekehrt (36). Einmal infiziert, scheiden Personen mit COVID-19 Viruspartikel aus, bevor, während und nachdem sie Symptome zeigen (37, 38). Diese Viruspartikel können sich dann auf unbelebten Objekten in der gebauten Umgebung absetzen und ein potentielles Übertragungsrisiko darstellen (18, 34, 39). Es gibt Hinweise darauf, dass mikrobentragende Objekte und Flächen mit SARS-CoV-2-Partikeln von infizierten Personen kontaminiert werden können, durch Körperflüssigkeiten wie Speichel und Nasensekret, durch den Kontakt mit verunreinigten Händen und durch das Absetzen von aerosolisierten Viruspartikeln und großen Tröpfchen, die beim Sprechen, Niesen, Husten und Erbrechen verbreitet werden (34, 40). Eine Studie zur Umgebungskontamination durch MERS-CoV ergab, dass fast jede berührbare Oberfläche in einem Krankenhaus mit MERS-CoV-Patienten durch das Virus kontaminiert war (41), und auch die Untersuchung eines Krankenhauszimmers mit einem unter Quarantäne gestellten COVID-19-Patienten zeigte eine umfangreiche Umgebungskontamination (18, 34). Aktuell wird immer mehr Wissen über die Übertragungsdynamik von COVID-19 gesammelt, und Studien zu SARS und MERS-CoV, vorläufige Daten zu SARS-CoV-2 sowie Empfehlungen der CDC legen den Schluss nahe, dass sich SARS-CoV-2 möglicherweise auf Objekten und Flächen halten kann, für einige Stunden bis hin zu fünf Tagen (39, 42, 43), je nach Material (43). Laut vorläufigen Studien zur Beständigkeit von SARS-CoV-2 überlebt das Virus am längsten bei einer relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit von 40 % auf Kunststoffoberflächen (mittlere Halbwertszeit: 15,9 h) und am kürzesten in Aerosolform (mittlere Halbwertszeit:2,74 h) (43); das Überleben in Aerosolen wurde jedoch bei einer relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit von 65 % bestimmt. Auf der Grundlage von Daten im Zusammenhang mit SARS und MERS gehen wir davon aus, dass SARS CoV 2 in Aerosolen bei einer niedrigeren relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit wahrscheinlich länger überleben kann. SARS-CoV-2 überlebt bei 40 % relativer Luftfeuchtigkeit auf Kupfer (mediane Halbwertszeit:13,4 h), Pappe (mediane Halbwertszeit: 8,45 h) und Stahl (mediane Halbwertszeit: 13,1 h) länger als in der Luft, jedoch weniger lang als auf Kunststoff (43). Es ist jedoch anzumerken, dass es bisher keine dokumentierten Fälle einer COVID-19-Infektion gibt, die von mikrobentragenden Objekten oder Flächen herrühren. Es gibt vorläufige Daten, die das Vorhandensein von SARS-CoV-2 in Stuhlproben belegen, was darauf hindeutet, dass die Übertragung möglicherweise auch fäkal-oral erfolgen kann (18, 29, 34, 44). Obwohl COVID-19-Infektionen bisher nur durch die Ausbreitung von Atemtröpfchen und nicht durch Ablagerungen auf Objekten oder Flächen dokumentiert wurden, sollten dennoch Schritte unternommen werden, um alle möglicherweise mit SARS-CoV-2 belasteten Oberflächen zu reinigen und zu desinfizieren, in der Annahme, dass das aktive Virus auch durch den Kontakt mit diesen unbelebten Materialien übertragen werden kann (34, 39). Um optimale Sicherheit zu garantieren, sollte daher unbedingt die Möglichkeit in Betracht gezogen werden, dass das Virus durch Aerosole und durch Oberflächen übertragen wird (45). Eine Konzeptualisierung der SARS-CoV-2-Ausscheidung zeigt Abb. 2.

ABBILDUNG 2

ABBILDUNG 2Konzeptualisierung der SARS-CoV-2-Ausscheidung. (a) Sobald eine Person mit SARS-CoV-2 infiziert ist, sammeln sich Viruspartikel in der Lunge und in den oberen Atemwegen an. (b) Tröpfchen und aerosolisierte Viruspartikel werden durch alltägliche Aktivitäten wie Husten, Niesen und Sprechen sowie durch nicht-routinemäßige Ereignisse wie Erbrechen aus dem Körper ausgeschieden und können sich in die nahe Umgebung und auf andere Personen ausbreiten (34, 40). (c und d) Viruspartikel, die aus Mund und Nase ausgeschieden werden, befinden sich häufig an den Händen (c) und können auf oft berührte Gegenstände (d) wie Computer, Brillen, Wasserhähne und Arbeitsplatten übertragen werden. Derzeit gibt es keine bestätigten Fälle einer Übertragung von mikrobenbelasteten Objekten und Flächen auf Menschen, doch es wurden Viruspartikel auf unbelebten Materialien in gebauten Umgebungen gefunden (34, 39, 42). Es wurde bereits nachgewiesen, dass SARS durch Tröpfchen übertragen werden kann und meist auch auf diese Weise übertragen wird (46). Da es sich bei SARS-CoV-2 um einen Schwester-Stamm des SARS-Virus aus dem Jahr 2002 – das bekanntermaßen von Mensch zu Mensch übertragen wird – handelt (47) und angesichts der hohen Inzidenz der beobachteten Übertragungen von Mensch zu Mensch sowie der raschen Ausbreitung von COVID-19 auf der ganzen Welt und in Gemeinden, besteht nun kein Zweifel mehr daran, dass SARS-CoV-2 auch durch Tröpfchen verbreitet werden kann (13, 48). Doch auf der Grundlage früherer Untersuchungen zu SARS (49) gilt die Übertragung durch Aerosolisierung weiterhin als sekundäre Übertragungsmethode, insbesondere innerhalb der gebauten Umwelt. Um eine Virusübertragung durch Luftzufuhrsysteme in gebauten Umgebungen zu vermeiden, werden in der Regel integrierte Filtermedien benötigt. Für Wohn- und Gewerbegebäude wird in der Regel ein Mindesteffizienzberichtswert (MERV) von 8 festgelegt, d. h. es müssen 70 bis 85 % aller Partikel mit einer Größe von 3,0 bis 10,0 μm abgefangen werden. Mit diesem Konzept lassen sich die Auswirkungen von Ablagerungen und Effizienzverlusten bei Kühlschlangen und anderen Heizungs-, Lüftungs- und Klimaanlagenkomponenten (HVAC) minimieren. Um die einströmende Außenluft auf der Grundlage der lokalen Außenpartikelwerte zu filtern, sind höhere MERV-Werte erforderlich. Für Räume mit Schutzatmosphäre in Krankenhäusern ist die strengste Mindestfiltereffizienz vorgeschrieben (50). Ein erster Filter mit einem MERV-Wert von 7 (MERV-7) oder höher muss den Heiz- und Kühlgeräten vorgelagert sein, und ein zweiter hocheffizienter Schwebstofffilter (HEPA-Filter) wird hinter den Kühlschlangen und Ventilatoren platziert. HEPA-Filter sind so ausgelegt, dass sie mindestens 99,97 % aller Partikel mit einer Größe von nur 0,3 μm abfangen (51). In den meisten Wohn- und Gewerbegebäuden kommen MERV-5- bis MERV-11-Filter zum Einsatz, in besonders sensiblen Gesundheitsumgebungen auch Anlagen mit einem Wert von MERV-12 oder mehr, oder HEPA-Filter. MERV-13-Filter haben das Potenzial, Mikroben und andere Partikel mit einer Größe von 0,3 bis 10,0 μm zu entfernen. Die meisten Viren, einschließlich der Coronaviren, haben eine Größe von 0,004 bis 1,0 μm. Daher ist die Wirksamkeit derartiger Filtrationstechniken gegen Krankheitserreger wie SARS-CoV-2 begrenzt (52). Außerdem ist kein Filtersystem perfekt. Kürzlich wurde festgestellt, dass Ritzen in den Rändern von Filtern ein Grund dafür waren, warum die Filtersysteme in Krankenhäusern bestimmte Erreger nicht aus der allgemeinen Atemluft entfernen konnten (53). In den vergangenen Jahren hat die Share Economy neue Umgebungen und Konzepte geschaffen, dank derer sich mehrere Menschen ein und dieselben Räume teilen können. Es ist möglich, dass die Übertragung von Infektionskrankheiten durch diesen Trend zur Share Economy beeinflusst wird. Gemeinsam genutzte Arbeitsräume (beispielsweise in Coworking-Spaces), Zimmer, Autos, Fahrräder und andere Elemente der gebauten Umwelt können die Wahrscheinlichkeit von durch die Umgebung vermittelten Infektion erhöhen und die Durchsetzung sozialdistanzierender Maßnahmen erschweren. Beispielsweise befand sich früher auch im Rahmen alternativer Transportkonzepte meist nur eine Person in einem Fahrzeug, heute dagegen bildet man häufig Fahrgemeinschaften oder nutzt Transportnetzwerke, wodurch sich das Gefährdungspotenzial erhöhen kann.

Maßnahmen zur Infektionsvermeidung in gebauten Umgebungen

Hinsichtlich der Ausbreitung von COVID-19 können sich Situationen sehr schnell ändern, doch sowohl innerhalb als auch außerhalb der gebauten Umwelt lassen sich Infektionsketten durch gezielte Maßnahmen unterbrechen. Auf der persönlichen Ebene spielt sorgfältiges Händewaschen eine entscheidende Rolle bei der Vermeidung von Infektionen mit SARS CoV-2, anderen Coronaviren und vielen Atemwegskeimen (54–56). Man sollte den Kontakt und die räumliche Nähe zu infizierten Personen meiden und sich häufig und mindestens 20 Sekunden lang die Hände mit Seife und heißem Wasser waschen (39). Da es sich zudem nur schwer feststellen lässt, wer infiziert ist und wer nicht, lassen sich Infektionsketten oft am besten unterbrechen, indem man große Ansammlungen von Einzelpersonen meidet, was auch als „Social Distancing“ bekannt ist. Zum jetzigen Zeitpunkt empfiehlt die Food and Drug Administration (FDA) nicht, dass symptomfreie Personen im Alltag hochwertige Masken tragen sollten, denn man möchte derartige Masken und Materialien für mit COVID-19 infizierte Personen sowie für medizinisches Personal und Familienangehörige, die in ständigem Kontakt mit COVID-19-Infizierten stehen, vorrätig halten (57). Darüber hinaus kann das Tragen einer Maske ein falsches Gefühl der Sicherheit vermitteln, wenn man sich in potenziell kontaminierten Bereichen bewegt, und die falsche Handhabung und Verwendung von Masken kann die Übertragungsgefahr sogar erhöhen (58). Sobald diese Masken jedoch in ausreichender Zahl verfügbar werden, wäre es ratsam, eine solche Maske zu tragen, wobei die Beschäftigten des Gesundheitswesens, die sich täglich in einer gefährdeteren Umgebung aufhalten, hier natürlich weiterhin Vorrang haben. Es gibt viele Hinweise darauf, dass eine Übertragung über die Luft (49) durch aerosolisierte Partikel auch über Entfernungen von mehr als 1,8 Metern hinweg möglich ist und dass eine Maske dabei helfen würde, Infektionen auf diesem Weg zu verhindern.

Seit Ende Januar 2020 haben viele Länder Reiseverbote erlassen, um Infektionen von Mensch zu Mensch und die partikelbasierte Übertragung zu verhindern. Diese Mobilitätseinschränkungen wurden erlassen, um die Verbreitung von COVID-19 einzudämmen (59). Auch innerhalb lokaler Gemeinschaften kann eine Vielzahl von Schritten unternommen werden, um eine weitere Ausbreitung zu verhindern (60). Derartige Maßnahmen sind als „Social Distancing außerhalb des Gesundheitswesens“ bekannt. Zu diesen gehört die Schließung von Bereichen mit hohem Personenaufkommen, wie beispielsweise Schulen und bestimmte Arbeitsumgebungen. Diese Maßnahmen auf Gemeindeebene verhindern die Übertragung von Krankheiten durch die gleichen Mechanismen wie die weltweiten Reisebeschränkungen, indem sie den typischen Kontakt von Mensch zu Mensch reduzieren, die Gefahr einer Kontamination von Oberflächen und Objekten durch Viruspartikel ausscheidende Personen verringern und die Wahrscheinlichkeit minimieren, dass infektiöse Partikel über die Luft andere im selben Raum oder in unmittelbarer Nähe befindliche Personen erreichen. Diese Entscheidungen werden von Einzelpersonen getroffen, die administrative Entscheidungsbefugnisse im Hinblick auf große Amtsbereiche, Gemeinde oder Gebäudekomplexe haben und die unter Berücksichtigung zahlreicher Faktoren – darunter Gesundheitsrisiken bzw. soziale und wirtschaftliche Auswirkungen – abwägen. Darüber hinaus werden auch in Zeiten erheblicher sozialer Distanzierungs- und Quarantänevorschriften bestimmte Gebäudetypen und Raumnutzungen als kritische und wesentliche Infrastruktur angesehen, wie z. B. Gesundheitseinrichtungen, Wohngebäude und Lebensmittelgeschäfte. Je besser die relevanten Faktoren im Hinblick auf gebaute Umgebungen verstanden wurden, desto einfacher sind Entscheidungen darüber, ob und für welche Dauer sozialdistanzierende Maßnahmen durchgeführt werden sollen. Dies gilt auch für Personen, die in Zeiten sozialer Distanzierung für den Baubetrieb und Umweltdienste im Zusammenhang mit essentieller und kritischer Infrastruktur verantwortlich sind, sowie für alle Gebäudearten vor und nach der Durchführung sozialdistanzierender Maßnahmen.

In der gebauten Umwelt können auch die Umgebung betreffende Maßnahmen ergriffen werden, um die Ausbreitung von SARS-CoV-2 zu verhindern, beispielsweise lassen sich Viruspartikel auf Oberflächen chemisch eliminieren (39). Es hat sich gezeigt, dass 62 bis 71-prozentiges Ethanol MERS-, SARS- (42) und SARS-CoV-2-Erreger zuverlässig vernichtet (34). Diese Ethanolkonzentration ist typisch für die meisten alkoholbasierten Handdesinfektionsmittel, die bei richtiger Anwendung somit gute Dienste bei der Bekämpfung von SARS-CoV-2 in gebauten Umgebungen leisten. Gegenstände sollten aus den Spülbeckenbereichen entfernt werden, um sicherzustellen, dass aerosolisierte Wassertropfen keine Viruspartikel auf häufig verwendete Gegenstände tragen, und die Arbeitsplatten um die Spülbecken herum sollten regelmäßig mit einer 10-prozentigen Bleichlösung oder einem alkoholhaltigen Reinigungsmittel behandelt werden. Auch hier darf man jedoch nicht vergessen, dass bei früheren Coronavirus-Ausbrüchen die Übertragung von Tröpfchen beim Sprechen, Niesen, Husten und Erbrechen als wichtigster und weitaus häufigerer Infektionsweg identifiziert wurde, und nicht der fäkal-orale Weg (34, 38, 39). Die Verwalter und Betreiber von Gebäuden sollten Schilder über die Wirksamkeit des mindestens 20 sekündigen Händewaschens mit Seife und heißem Wasser anbringen, stets gefüllte Seifenspender aufstellen, den Zugang zu alkoholbasierten Händedesinfektionsmitteln ermöglichen und Protokolle für die routinemäßige Reinigung von Oberflächen mit hohem Kontaminationsrisiko (beispielsweise in der Nähe von Waschbecken und Toiletten) einführen (39). Um die Übertragung von Mikroben und damit unerwünschter Krankheitserreger zu verhindern, ist es vor allem wichtig, eine angemessene Hand-Hygiene zu gewährleisten (39, 61).

Die Einführung verbesserter Betriebsverfahren im Bereich der Heiz- und Klimatechnik in Gebäuden kann das Ausbreitungspotenzial von SARS-CoV-2 ebenfalls verringern. Auch wenn die Viruspartikel zu klein sind, um selbst von den besten HEPA- und MERV-Filtern zurückgehalten zu werden, können Vorkehrungen im Bereich der Belüftung die Ausbreitung von SARS-CoV-2 minimieren. Ordnungsgemäß eingebaute und gewartete Filter können das Risiko einer Übertragung über die Luft verringern – wohlgemerkt jedoch nicht ganz eliminieren. Ein höherer Außenluftanteil und verstärkte Luftaustauschraten in Gebäuden können in gebauten Umgebungen die Konzentration von Schadstoffen (einschließlich Viren) in der Innenraum-Atemluft verringern. Höhere Außenluftanteile können erreicht werden, indem man die Außenluftklappen an den Lüftungsanlagen besonders weit öffnet, sodass mehr Raumluft und damit auch eventuell vorhandene luftgetragene Viren abgesaugt werden (62). In Bezug auf diese Parameter des Gebäudebetriebs sind jedoch einige Vorsichtsmaßnahmen zu beachten. Erstens kann ein höherer Außenluftanteil den Energieverbrauch steigern. Über kürzere Zeiträume hinweg wird sich diese Maßnahme zum Schutz der Gesundheit sicherlich lohnen, doch der Gebäudebetreiber wird mit dem Ende der Risikoperiode möglichst schnell zu normalen Verhältnissen zurückkehren wollen. Zweitens haben nicht alle Lüftungsanlagen die Kapazität, um den Außenluftanteil nennenswert zu erhöhen, und bei denjenigen, die dies können, müssen die Filter möglicherweise häufiger gewartet werden. Drittens könnte die Übertragungsgefahr sogar steigen, wenn durch eine Intensivierung des Luftstromes lediglich die vorhandene Luft verstärkt umgewälzt und keine frische Luft von außen zugeführt wird. Bei höheren Luftstromgeschwindigkeiten könnten mehr Mikroben von belasteten Objekten und Flächen aufgenommen werden, sodass sich das Kontaminationspotenzial im gesamten Gebäude erhöht, wenn die Raumluft schneller und in größeren Mengen verteilt wird und möglicherweise mehr ultrafeine Partikel resuspendiert werden (62). Darüber hinaus könnte eine Erhöhung der Raumluftzirkulationsrate die Menschen im Gebäude mit noch mehr lebensfähigen luftgetragenen Viren in Kontakt bringen, die von anderen Gebäudenutzern ausgeschieden werden. Die Verwalter und Betreiber von Gebäuden sollten daher gemeinsam in Erfahrung bringen, ob eine Erhöhung des Außenluftanteils sinnvoll ist und welche Nachteile oder indirekten Auswirkungen zu berücksichtigen sind, ehe sie einen Plan zur Regulierung des Außenluftanteils und der Luftaustauschraten ausarbeiten. Es gibt immer mehr Hinweise darauf, dass Feuchtigkeit eine Rolle für das Überleben membrangebundener Viren wie SARS-CoV-2 spielt (63–65). Frühere Forschungen haben ergeben, dass viele Viren, einschließlich der Coronaviren, bei typischen Innentemperaturen und einer relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit von über 40 % im Allgemeinen weniger gut überleben können (63, 66, 67), zudem reduzierte eine höhere relative Luftfeuchtigkeit in Innenräumen bei simuliertem Hustentests nachweislich die Infektiosität von Grippeviren (67). Laut den Erkenntnissen aus Studien mit anderen Viren, darunter auch Coronaviren, verringert eine höhere relative Feuchtigkeit auch die Ausbreitung in der Luft, da größere Tröpfchen, die Viruspartikel enthalten, zurückgehalten werden, wodurch sie sich schneller auf Raumoberflächen ablagern (63, 68, 69). Eine höhere Luftfeuchtigkeit schädigt lipidumhüllte Viren (zu denen auch die Coronaviren zählen) vermutlich durch Wechselwirkungen mit den polarisierten Membranfortsätzen, sodass sich die chemische Zusammensetzung der Membran verändert und das Virus abgetötet wird (70, 71). Darüber hinaus können Veränderungen der Luftfeuchtigkeit einen Einfluss darauf haben, wie anfällig eine Person für eine Infektion mit Viruspartikeln ist (72) und wie weit die Viren in die Atemwege vordringen (68). Eine verminderte relative Luftfeuchtigkeit dagegen verringert nachweislich das Ausscheiden eindringender Krankheitserreger über den körpereigenen Schleim und schwächt die angeborene Immunabwehr (72–74). Eine relative Luftfeuchtigkeit von mehr als 80 % kann jedoch zu einer verstärkten Schimmelbildung führen, was potenziell schädliche Auswirkungen auf die Gesundheit haben kann (75). Obwohl der aktuelle Belüftungsstandard für Gesundheits- und Pflegeeinrichtungen (ASHRAE 170-2017) im Hinblick auf die relative Luftfeuchtigkeit einen breiteren Bereich von 20 bis 60 % zulässt, empfiehlt es sich unter Umständen, die relative Luftfeuchtigkeit dauerhaft auf einen Bereich von 40 bis 60 % einzustellen, um die Ausbreitung und das Überleben von SARS-CoV-2 innerhalb der gebauten Umgebung zu begrenzen, das Schimmel-Risiko zu minimieren und die Schleimhautbarrieren der menschlichen Nutzer in einem ausreichend feuchten und intakten Zustand zu halten (50, 67). Die Raumluftbefeuchtung wurde bei den meisten HVAC-Systemkonzepten nicht berücksichtigt, was vor allem auf die Kosten der Ausstattung und auf Bedenken hinsichtlich der Wartung im Zusammenhang mit dem Risiko einer Überbefeuchtung, welche die Gefahr einer Schimmelbildung erhöht, zurückzuführen ist. Zwar sollten die Verwalter und Betreiber von Gebäuden die Kosten, Vorteile und Risiken einer zentralen Befeuchtungsanlage in Betracht ziehen (insbesondere bei Neubauten oder als Nachrüstungsoption), doch kann dies als Reaktion auf einen spezifischen Virusausbruch oder eine Virusepisode zu zeitintensiv sein. Darüber hinaus kann eine erhöhte relative Luftfeuchtigkeit zu einer verstärkten Ablagerung auf Filtern führen, wodurch der Luftstrom abnimmt. In Pandemiesituationen jedoch erleichtert dieses Vorgehen wahrscheinlich das Auffangen von Viruspartikeln, und dieser Vorteil überwiegt den erhöhten Wartungsaufwand des Filters. Daher ist eine gezielte Raumluftbefeuchtung eine weitere Option, die in Betracht gezogen werden sollte – zudem kann sie die Wahrscheinlichkeit verringern, dass ein Wartungsfehler zu einer Überbefeuchtung führt.

Die Quelle der Gebäudelüftung und die Länge des Verteilungsweges können die Zusammensetzung der mikrobiellen Gemeinschaften in Innenräumen beeinflussen. Die Belüftung eines Gebäudes durch Einleiten von Luft direkt durch die Fassade in angrenzende Räume ist eine Strategie, wenn man sich nicht auf die Wirksamkeit einer Filtration des gesamten Gebäudes verlassen will, um die Verbreitung von Mikroorganismen im System zu verhindern. Es hat sich gezeigt, dass die direkte Zufuhr von Außenluft durch die Fassade in ein angrenzendes Raumvolumen die phylogenetische Vielfalt von Bakterien- und Pilzgemeinschaften in Innenräumen erhöht und Gemeinschaften schafft, die den im Freien lebenden Mikroben ähnlicher sind als denjenigen in einer Luft, die durch ein zentralisiertes HVAC-System zugeführt wurde (76). In einigen Gebäuden kann ein ähnlicher Ansatz durch verteilte HVAC-Einheiten realisiert werden, wie z. B. verpackte Terminalklimaanlagen (PTAC), die häufig in Hotels, Motels, Seniorenheimen, Eigentumswohnungen und Apartments zu finden sind, oder durch passive Belüftungsstrategien an der Fassade, wie z. B. gedämpfte Belüftungsöffnungen (77, 78). Bei den meisten Gebäuden ist es jedoch am einfachsten, die Außenluft direkt durch das Gebäude zu leiten, indem man ein Fenster öffnet. Die Fensterlüftung umgeht nicht nur die Lüftungskanäle, sondern erhöht auch den Anteil der Außenluft und den Gesamtluftaustausch (79). Die Verwalter und Betreiber von Gebäuden sollten einen Plan zur Verbesserung der Belüftung über die Fassade und insbesondere die Fenster erarbeiten, sofern die Außentemperaturen dies zulassen. Es sollte darauf geachtet werden, dass die Bewohner keinen extremen Temperaturschwankungen ausgesetzt sind, und Vorsicht ist geboten, wenn die räumliche Nähe eine Virenübertragung von einer Wohnung zur nächsten begünstigen würde (94, 95).

Lichteinwirkung ist ein weiteres Mittel zur Verringerung der Lebensfähigkeit bestimmter infektiöser Erreger in Innenräumen. Tageslicht ist ein allgegenwärtiges und bestimmendes Element in der Architektur: Im Rahmen von Mikrokosmos-Studien hat sich gezeigt, dass es in Hausstaub vorkommende Bakterien verändert, sodass diese sich weniger gut im Menschen verbreiten als es in dunkleren Räumen der Fall wäre (80). Darüber hinaus reduzierte Tageslicht sowohl im UV- als auch im sichtbaren Spektralbereich die Lebensfähigkeit von Bakterien, was anhand von Vergleichen mit Kontrollproben aus dunkleren Mikrokosmosräumen bestätigt wurde (80). In einer Studie, die Sonnenlicht auf Influenzavirus-Aerosolen simulierte, ließ sich die Halbwertszeit des Virus signifikant reduzieren, von 31,6 Minuten in der Dunkelheits-Kontrollgruppe auf etwa 2,4 Minuten im simulierten Sonnenlicht (81). In Gebäuden wird ein Großteil des Sonnenlichtspektrums durch Architektur-Fensterglas gefiltert, und das hindurchgelassene UV-Licht wird von den Oberflächen weitgehend absorbiert und nicht tiefer in den Raum reflektiert. Daher sind weitere Forschungsarbeiten erforderlich, um den Einfluss von natürlichem Licht auf SARS-CoV-2 in Innenräumen zu verstehen; bis dahin ist Tageslicht jedoch eine kostenlose, frei verfügbare Ressource für die Gebäudenutzer und hat nur geringe Nachteile, jedoch viele dokumentierte positive Auswirkungen auf die menschliche Gesundheit (80–83). Um reichlich Tages- und Sonnenlicht hereinzulassen, sollten die Verwalter und Betreiber von Gebäuden daher dazu aufrufen, Jalousien und Rollläden zu öffnen, wann immer diese nicht benötigt werden (um Blendeffekte zu vermeiden, die Privatsphäre zu schützen oder den Komfort der Nutzer aus anderen Gründen zu erhöhen).

Während die Wirkung von Tageslicht auf Innenraum-Viren und SARS-CoV-2 noch unerforscht ist, wird spektral abgestimmtes elektrisches Licht bereits als technisches Mittel für die Desinfektion in Innenräumen eingesetzt. UV-Licht im Bereich kürzerer Wellenlängen (254 nm UV C [UVC]) ist besonders keimtötend, und auf diesen Teil des Lichtspektrums abgestimmte Vorrichtungen werden in klinischen Einrichtungen wirksam eingesetzt, um infektiöse Aerosole zu inaktivieren und um die Überlebensfähigkeit bestimmter Viren zu verringern (84). Dabei ist zu berücksichtigen, dass der Großteil des UVC-Lichtes in der Atmosphäre eliminiert wird, während das UVA- und UVB-Spektrum teilweise durch die Gebäude-Glasschichten ausgefiltert wird. Die Zahl der durch die Luft übertragenen Viren, die einsträngige RNA (ssRNA) enthalten, lässt sich bereits mit einer niedrigen Dosis UV-Licht um 90 % reduzieren, bei RNA-Viren auf Oberflächen wird dagegen eine höhere UV-Dosis benötigt (85, 86). Eine frühere Studie hat gezeigt, dass eine zehnminütige Bestrahlung mit UVC-Licht bereits 99,999 % der überprüften Coronaviren (SARS-CoV und MERS-CoV) eliminierte (87). Keimtötende UV-Strahlung (UVGI) ist möglicherweise jedoch nicht ganz ungefährlich, wenn die Personen im Raum hochenergetischem Licht ausgesetzt werden. Aus diesem Grund werden die UVGI Quellen in mechanischen Lüftungswegen oder in Systemen im oberen Raumbereich installiert, um die Luft indirekt und gefahrlos durch konvektive Luftbewegungen zu behandeln (88, 89). Vor Kurzem hat sich gezeigt, dass weit entferntes UVC-Licht im Bereich von 207 bis 222 nm luftgetragene aerosolisierte Viren wirksam eliminieren kann. Zwar deuten vorläufige Ergebnisse aus In-vivo- Nagetier-Modellen und dreidimensionale (3-D) In-vitro-Modelle menschlicher Haut darauf hin, dass keine Schäden an der Haut und den Augen von Personen zu befürchten sind (90, 91), dennoch muss die Sicherheitsmarge im Rahmen weiterer Untersuchungen überprüft werden, ehe dieses Verfahren in die Tat umgesetzt werden kann. Wenn es sicher eingesetzt werden kann, lassen sich mithilfe von UVC- und UVGI-Licht eine ganze Reihe potenzieller Desinfektionsstrategien für Gebäude und für eine Tiefenreinigung im Gesundheitswesen realisieren. Eine gezielte UVC- und UVGI-Desinfektion kann in verschiedenen Arten von Räumen, in denen sich positiv auf COVID-19 getestete Personen aufgehalten haben, angebracht sein, doch ein routinemäßiger Einsatz dieses Verfahrens kann unbeabsichtigte Folgen haben und kommt nur bei entsprechenden Vorsichtsmaßnahmen infrage.

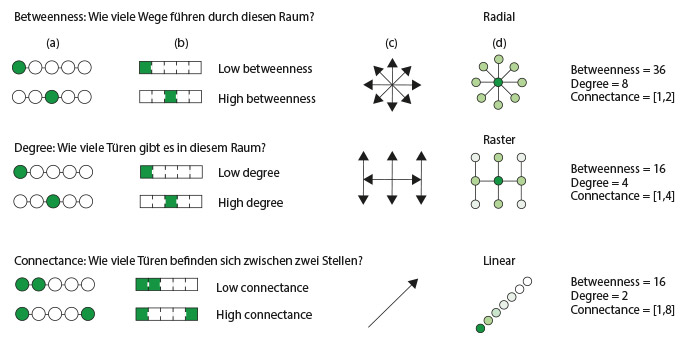

Die räumliche Anordnung von Gebäuden kann soziale Interaktionen fördern oder erschweren. In den vergangenen Jahren hat die westliche Gesellschaft ein Baukonzept bevorzugt, das visuelle Transparenz und ein Gefühl von „Geräumigkeit“ in Innenräumen betont, sei es zu Hause in Form von Großraumkonzepten oder am Arbeitsplatz, wo eine offene Büroraumplanung mit weitläufigen Layouts die Anwesenden bewusst auf Knotenpunkte „zufälliger Begegnungen“ lenkt, um die Zusammenarbeit und den Ideenaustausch unter den Mitarbeitern zu fördern. Zwar haben diese räumlichen Konfigurationen aus kultureller Sicht viele Vorteile, doch sie können unbeabsichtigt die Gefahr einer Übertragung von Viren durch gezielte menschliche Interaktion erhöhen. Ein Grund hierfür ist, dass große, hoch frequentierte offene Büroräume – ganz im Gegensatz zum Einzelbüro – den direkten Kontakt zwischen den Beschäftigten fördern. Die Raumsyntaxanalyse zeigt eine Beziehung zwischen der räumlichen Disposition und der Intensität des persönlichen Kontaktes (Abb. 3) – dieses Verhältnis korreliert nachweislich mit der Häufigkeit und Vielfalt von Mikroben in einem bestimmten Raum (92). Das Verständnis dieser räumlichen Konzepte könnte Teil des Entscheidungsprozesses sein, ob sozialdistanzierende Maßnahmen umgesetzt werden sollen, in welchem Umfang die Personendichte begrenzt werden soll und wie lange die Maßnahmen aufrechterhalten werden sollen.

ABBILDUNG 3

ABBILDUNG 3Grafiken zur räumlichen Konnektivität, die das Verhältnis zwischen Trennendem und Verbindendem in gemeinsam genutzten Räumen und im Hinblick auf Türanordnungen verdeutlichen. (a) Bei den Kreisen und Linien handelt es sich um eine klassische Netzwerkdarstellung. (b) Die Rechtecke verdeutlichen die Übertragung in ein architektonisches Netzwerkkonzept. Die farbliche Abstufung dient als Maß für das „Dazwischensein“ (die Anzahl der kürzesten Wege zwischen allen Raumpaaren, die durch einen gegebenen Raum führen, über die Summe aller kürzesten Wege zwischen allen Raumpaaren im Gebäude), die Intensität (die Anzahl der Verbindungen eines Raumes zu anderen Räumen zwischen zwei beliebigen Räumen) und die Verbundenheit (die Anzahl der Türen zwischen zwei beliebigen Räumen). (c) Die Pfeile stellen mögliche Richtungen der Ausbreitung von Mikroben dar, die durch die Aufteilung der gebauten Umgebung bestimmt werden. (d) Die Kreise repräsentieren den aktuellen Wissensstand über die mikrobielle Ausbreitung auf der Grundlage der durch die Raumaufteilung bestimmten Keimkonzentrationen in der gebauten Umgebung. Dunklere Farben stehen für eine höhere Keimkonzentration, hellere Farben für eine niedrigere. Besondere Überlegungen hinsichtlich der Gesundheitsversorgung bei aktuellen und zukünftigen Epidemien

Krankenhäuser stellen einzigartige Herausforderungen dar, wenn es darum geht, den Ausbruch einer Infektionskrankheit einzudämmen und alle in ihnen befindlichen Personen vor dem Ausbruch zu schützen. Gesundheits- und Krankenhauseinrichtungen haben nicht nur begrenzte Möglichkeiten für sozialdistanzierende Maßnahmen zur Verhinderung der Ausbreitung von Infektionen, sondern beherbergen oft auch Patienten, die ganz unterschiedliche Anforderungen an die gebaute Umgebung um sie herum stellen. Beispielsweise werden Hochrisikopatienten mit geschwächtem Immunsystem häufig in Räumen mit Schutzatmosphäre untergebracht, die so konzipiert sind, dass durch die Außenluft übertragene Krankheitserreger nicht in den Raum gelangen können. Zu diesem Zweck werden diese Räume im Vergleich zu den Fluren unter einen positiven Druck gesetzt (ASHRAE 170-2017 [50]), und es wird nur ein Minimum an HEPA-Luft zugeführt. Dieser Druckunterschied erhöht jedoch auch die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass Aerosole im Patientenzimmer bei geöffneter Tür aus dem Raum mit Schutzatmosphäre hinaus und in den höher frequentierten Flurbereich wandern. Da Räume mit Schutzatmosphäre auf die Bedürfnisse ihres Nutzers ausgelegt sind, könnten die Maßnahmen zur Begrenzung des Eindringens von Krankheitserregern in den Raum jedoch möglicherweise zu einer unfreiwilligen Infektionsgefahr für das medizinische Personal, andere Patienten und Besucher in den Fluren führen, wenn ein immungeschwächter Patient auch mit einer durch die Luft übertragbaren Krankheit infiziert ist. Im Gegensatz dazu wird der Druck in Zimmern zur Isolierung von Patienten mit luftübertragenen Infektionen (Airborne Infection Isolation, AII) niedriger gehalten als in den Fluren und den angrenzenden Räumen, wobei die Raumluft direkt nach außen abgesaugt wird, um aerosolisierte Krankheitserreger von der Ausbreitung in Zirkulations- und Gemeinschaftsräume abzuhalten. Derselbe Unterdruck, der die Verbreitung von aerosolisierten Krankheitserregern aus dem Rauminneren hinaus verhindert, kann nun jedoch die im Zimmer befindlichen Personen unfreiwillig luftübertragenen Krankheitserregern aussetzen, die von den Personen auf den Fluren stammen. Sowohl Räume mit Schutzatmosphäre als auch AII-Zimmer können daher mit einem Vorraum ausgestattet werden, der als zusätzlicher Puffer zwischen Gemeinschaftsbereichen und den geschützten Räumen dient, um die Ausbreitung von Krankheitserregern zu verhindern; der Vorraum dient häufig auch als Bereich, in dem das Krankenhauspersonal die persönliche Schutzausrüstung (PSA) an- und ablegen kann. Derartige Schleusen sind jedoch für Räume mit Schutzatmosphäre und für AII-Zimmer nicht zwingend erforderlich und haben im Routinebetrieb Nachteile; daher sind sie nur in bestimmten Einrichtungen vorhanden. Sie beanspruchen eine erhebliche zusätzliche Bodenfläche, verlängern die zurückzulegenden Wegstrecken und erhöhen die visuelle Barriere zwischen Patient und Behandlungsteam, was letztlich auch die Kosten erhöht. Derartige Kompromisse könnten angesichts der hohen Kosten von Pandemien und der kritischen Rolle von Gesundheitseinrichtungen in diesen Zeiten bei künftigen Entwurfs- und Einsatzprotokollen berücksichtigt werden.

Bei der Diskussion über Räume mit Schutzatmosphäre und AII-Zimmer wird jedoch die Mehrzahl der Patientenzimmer – die nicht notwendigerweise für die Eindämmung luftübertragener Atemwegsviren konzipiert sind – innerhalb eines Krankenhauses oder einer Gesundheitseinrichtung nicht angemessen berücksichtigt. Die allgemeine Gestaltung der Einrichtungen sollte überdacht werden, um die verschiedenen Anforderungen im Hinblick auf unterschiedliche Patientenbedürfnisse und Betriebsanforderungen sowohl unter Routinebedingungen als auch bei Pandemie-Ausbrüchen zu erfüllen. Eine solche Überlegung betrifft die Trennung der Systeme zur thermischen Raumkonditionierung von den Systemen für die Belüftung. Die Entkopplung dieser Funktionen ermöglicht dezentrale mechanische oder passive Lüftungssysteme, die in Multifunktionsfassaden mit Wärmerückgewinnung und 100 % Außenluftzufuhr integriert sind. Eine mechanische Luftzufuhr durch die Fassade würde es ermöglichen, alle Patientenzimmer isoliert zu betreiben und individuell anzupassen: In Abhängigkeit von den Bedürfnissen des Patienten ließe sich in ihnen somit ein höherer oder ein niedrigerer Luftdruck erzeugen, sodass sie im Hinblick auf die Abläufe unabhängiger würden. Darüber hinaus sollte bei künftigen Entwürfen berücksichtigt werden, wie die Klassifizierung und die umfassende Erstbeurteilung von Patienten, die Symptome einer Infektion mit durch die Luft übertragenen Viren aufweisen, am besten durchgeführt werden kann, um die Ansteckungsgefahr in Bereichen mit anderen Patientengruppen möglichst gering zu halten. Bei der Planung für die Zukunft sollten Architekten, Raumausstatter, Gebäudebetreiber und Verwaltungsverantwortliche im Gesundheitswesen Krankenhausentwürfe bevorzugen, die auch für Zeiten einer stärkeren sozialen Distanzierung geeignet sind und die die Verbindung und den Austausch zwischen Gemeinschaftsbereichen auf ein Minimum reduzieren können, während sie gleichzeitig genug Flexibilität für eine effiziente Raumnutzung unter normalen Betriebsbedingungen bieten.

Schlussfolgerung

Die Anzahl der Personen, die sich mit COVID-19 infiziert haben oder mit dem Virus SARS-CoV-2 in Kontakt kamen, steigt dramatisch an. Es wurden mikrobiologische Forschungsarbeiten im BE-Bereich aus mehr als einem Jahrzehnt ausgewertet, um aktuelle Erkenntnisse hinsichtlich der Überwachung und des Zustandekommens häufiger Pathogenübertragungswege und -mechanismen in gebauten Umgebungen zu gewinnen, die möglichst genau auf SARS-CoV-2 zutreffen. Wir hoffen, dass diese Informationen den Unternehmen, Bundes-, Landes-, Kreis- und Stadtverwaltungen, Universitäten, Schulbezirken, Gotteshäusern, Gefängnissen, Gesundheitseinrichtungen, Organisationen für betreutes Wohnen, Kindertagesstätten, Hausbesitzern und anderen Gebäudeeigentümern bzw. -nutzern dabei helfen, mittels informierter Entscheidungen und fundierter Infektionsvermeidungsmaßnahmen das Übertragungspotenzial im Rahmen eines Built-Environment-Konzeptes zu minimieren. Zudem sollen diese Informationen Unternehmen sowie öffentlichen Verwaltungen und Privatpersonen, die für den Bau und den Betrieb von Gebäuden verantwortlich sind, Entscheidungen bezüglich des Ausmaßes und der Dauer sozialdistanzierender Maßnahmen während viraler Epidemien und Pandemien erleichtern.

Dr. med. Walter J. Hugentobler

Diese Literaturübersicht enthält wertvolle Informationen für Gebäudebetreiber zu Maßnahmen, die sie zur Eindämmung der Verbreitung von COVID-19 ergreifen können.

Neben den regelmäßigen Ratschlägen, die wir von Regierungen zum Händewaschen und zur sozialen Distanzierung erhalten, zeigen die Ergebnisse, dass eine Erhöhung der Luftaustauschrate, eine Aufrechterhaltung der Luftfeuchtigkeit in Innenräumen von 40-60% r. F. (im Winter ohne aktive Befeuchtung nicht erreichbar) und eine Erhöhung des natürlichen Lichts eine positive Rolle spielen können.

Die wissenschaftlichen Studien, auf die in dieser Literaturübersicht verwiesen wird, liefern wertvolle Erkenntnisse darüber, wie wir eine gesünder gebaute Umwelt schaffen können, nicht nur in Krisenzeiten, sondern auch in unserem täglichen Leben. Wenn beispielsweise Krankenhäuser und öffentliche Einrichtungen ihre Luftfeuchtigkeit in Innenräumen auf der empfohlenen relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit von 40-60% halten würden, könnten jedes Jahr viele Menschenleben allein durch eine verringerte Grippeübertragung gerettet werden.

Quellen

Originaltitel: 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Built Environment Considerations To Reduce Transmission

Quellenlink: https://msystems.asm.org/content/5/2/e00245-20#ref-list-1

Veröffentlicht: März 2020

1. Parrish CR, Holmes EC, Morens DM, Park E-C, Burke DS, Calisher CH, Laughlin CA, Saif LJ, Daszak P. 2008. Cross-species virus transmission and the emergence of new epidemic diseases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72:457–470. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00004-08.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

2. de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS, Brown CS, Drosten C, Enjuanes L, Fouchier RAM, Galiano M, Gorbalenya AE, Memish ZA, Perlman S, Poon LLM, Snijder EJ, Stephens GM, Woo PCY, Zaki AM, Zambon M, Ziebuhr J. 2013. Commentary: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol 87:7790–7792. doi:10.1128/JVI.01244-13.FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

3. Peiris JSM, Lai ST, Poon LLM, Guan Y, Yam LYC, Lim W, Nicholls J, Yee WKS, Yan WW, Cheung MT, Cheng VCC, Chan KH, Tsang DNC, Yung RWH, Ng TK, Yuen KY, SARS Study Group. 2003. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 361:1319–1325. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

4. Hui DSC, Chan MCH, Wu AK, Ng PC. 2004. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): epidemiology and clinical features. Postgrad Med J 80:373–381. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.020263.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

5. World Health Organization. 5 January 2020. Pneumonia of unknown cause – China. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.Google Scholar

6. Peeri NC, Shrestha N, Rahman MS, Zaki R, Tan Z, Bibi S, Baghbanzadeh M, Aghamohammadi N, Zhang W, Haque U. 22 February 2020. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol doi:10.1093/ije/dyaa033.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

7. Ramadan N, Shaib H. 2019. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): a review. Germs 9:35–42. doi:10.18683/germs.2019.1155.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

8. Wu P, Hao X, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Leung KSM, Wu JT, Cowling BJ, Leung GM. 2020. Real-time tentative assessment of the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus infections in Wuhan, China, as at 22 January 2020. Euro Surveill 25:2000044. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000044.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

9. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Li M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JTK, Gao GF, Cowling BJ, Yang G, Leung GM, Feng Z. 29 January 2020. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

10. Rothan HA, Byrareddy SN. 26 February 2020. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J Autoimmun doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102433.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

11. Sizun J, Yu MW, Talbot PJ. 2000. Survival of human coronaviruses 229E and OC43 in suspension and after drying on surfaces: a possible source of hospital-acquired infections. J Hosp Infect 46:55–60. doi:10.1053/jhin.2000.0795.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

12. Chen Y, Liu Q, Guo D. 2020. Emerging coronaviruses: genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. J Med Virol 92:418–423. doi:10.1002/jmv.25681.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

13. Chan J-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H, To KK-W, Chu H, Yang J, Xing F, Liu J, Yip CC-Y, Poon R-S, Tsoi H-W, Lo S-F, Chan K-H, Poon V-M, Chan W-M, Ip JD, Cai J-P, Cheng V-C, Chen H, Hui C-M, Yuen K-Y. 2020. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet 395:514–523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

14. Fehr AR, Perlman S. 2015. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol 1282:1–23. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

15. Walls AC, Park Y-J, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. 2020. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 180:1–12.Google Scholar

16. South China Agricultural University. 2020. Pangolin is found as a potential intermediate host of new coronavirus in South China Agricultural University. https://scau.edu.cn/2020/0207/c1300a219015/page.htm.Google Scholar

17. Cui J, Li F, Shi Z-L. 2019. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:181–192. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

18. Perlman S. 2020. Another decade, another coronavirus. N Engl J Med 382:760–762. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001126.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

19. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, Niu P, Zhan F, Ma X, Wang D, Xu W, Wu G, Gao GF, Tan W, China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. 2020. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 382:727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

20. CDC. 2020. 2019-nCoV real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel (CDC) - fact sheet for healthcare providers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.Google Scholar

21. Millán-Oñate J, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Camacho-Moreno G, Mendoza-Ramírez H, Rodríguez-Sabogal IA, Álvarez-Moreno C. A new emerging zoonotic virus of concern: the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Infectio, in press.Google Scholar

22. Horve PF, Lloyd S, Mhuireach GA, Dietz L, Fretz M, MacCrone G, Van Den Wymelenberg K, Ishaq SL. 2020. Building upon current knowledge and techniques of indoor microbiology to construct the next era of theory into microorganisms, health, and the built environment. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 30:219–217. doi:10.1038/s41370-019-0157-y.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23. Adams RI, Bhangar S, Dannemiller KC, Eisen JA, Fierer N, Gilbert JA, Green JL, Marr LC, Miller SL, Siegel JA, Stephens B, Waring MS, Bibby K. 2016. Ten questions concerning the microbiomes of buildings. Build Environ 109:224–234. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.09.001.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

24. Tellier R, Li Y, Cowling BJ, Tang JW. 2019. Recognition of aerosol transmission of infectious agents: a commentary. BMC Infect Dis 19:101. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-3707-y.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

25. Andrews JR, Morrow C, Walensky RP, Wood R. 2014. Integrating social contact and environmental data in evaluating tuberculosis transmission in a South African township. J Infect Dis 210:597–603. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiu138.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

26. Mizumoto K, Chowell G. 2020. Transmission potential of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) onboard the Diamond Princess Cruises Ship, 2020. Infect Dis Model 5:264–270. doi:10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.003.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

27. Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. 2020. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 395:689–697. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

28. Zhang S, Diao M, Yu W, Pei L, Lin Z, Chen D. 2020. Estimation of the reproductive number of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and the probable outbreak size on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: a data-driven analysis. Int J Infect Dis 93:201–204. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.033.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

29. Poon LLM, Peiris M. 2020. Emergence of a novel human coronavirus threatening human health. Nat Med 26:317–319. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0796-5.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

30. Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, Heffernan J, Deeks SL, Li Y, Crowcroft NS. 2017. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 17:e420–e428. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30307-9.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

31. Biggerstaff M, Cauchemez S, Reed C, Gambhir M, Finelli L. 2014. Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 14:480. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-480.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

32. Zhao S, Cao P, Gao D, Zhuang Z, Chong MKC, Cai Y, Ran J, Wang K, Yang L, He D, Wang MH. 20 February 2020. Epidemic growth and reproduction number for the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak on the Diamond Princess Cruise Ship from January 20 to February 19, 2020: a preliminary data-driven analysis. SSRN doi:10.2139/ssrn.3543150.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

33. Mizumoto K, Kagaya K, Zarebski A, Chowell G. 2020. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Euro Surveill 25(10):pii=2000180. https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180.Google Scholar

34. Ong SWX, Tan YK, Chia PY, Lee TH, Ng OT, Wong MSY, Marimuthu K. 2020. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. JAMA doi:10.1001/jama.2020.3227.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

35. Stephens B, Azimi P, Thoemmes MS, Heidarinejad M, Allen JG, Gilbert JA. 2019. Microbial exchange via fomites and implications for human health. Curr Pollution Rep 5:214. doi:10.1007/s40726-019-00126-3.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

36. Vandegrift R, Fahimipour AK, Muscarella M, Bateman AC, Van Den Wymelenberg K, Bohannan B. 26 March 2019. Moving microbes: the dynamics of transient microbial residence on human skin. bioRxiv doi:10.1101/586008.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

37. Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, Zimmer T, Thiel V, Janke C, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Drosten C, Vollmar P, Zwirglmaier K, Zange S, Wölfel R, Hoelscher M. 2020. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med 382:970–971. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001468.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

38. Yaqian M, Lin W, Wen J, Chen G. 2020. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV: a system review. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS). medRxiv doi:10.1101/2020.02.20.20025601.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

39. CDC. 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.Google Scholar

40. Doultree JC, Druce JD, Birch CJ, Bowden DS, Marshall JA. 1999. Inactivation of feline calicivirus, a Norwalk virus surrogate. J Hosp Infect 41:51–57. doi:10.1016/S0195-6701(99)90037-3.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

41. Bin SY, Heo JY, Song M-S, Lee J, Kim E-H, Park S-J, Kwon H-I, Kim SM, Kim Y-I, Si Y-J, Lee I-W, Baek YH, Choi W-S, Min J, Jeong HW, Choi YK. 2016. Environmental contamination and viral shedding in MERS patients during MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea. Clin Infect Dis 62:755–760. doi:10.1093/cid/civ1020.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

42. Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. 2020. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and its inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect 104:246–251. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

43. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ. 2020. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med doi:10.1056/NEJMc2004973.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

44. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. 2020. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

45. Lipsitch M, Allen J. 16 March 2020. Coronavirus reality check: 7 myths about social distancing, busted. USA Today, McLean, VA. https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2020/03/16/coronavirus-social-distancing-myths-realities-column/5053696002/.Google Scholar

46. Bell DM, World Health Organization Working Group on International and Community Transmission of SARS. 2004. Public health interventions and SARS spread, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis 10:1900–1906. doi:10.3201/eid1011.040729.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

47. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2020. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

48. Chang D, Xu H, Rebaza A, Sharma L, Dela Cruz CS. 2020. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med 8:e13. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30066-7.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

49. Booth TF, Kournikakis B, Bastien N, Ho J, Kobasa D, Stadnyk L, Li Y, Spence M, Paton S, Henry B, Mederski B, White D, Low DE, McGeer A, Simor A, Vearncombe M, Downey J, Jamieson FB, Tang P, Plummer F. 2005. Detection of airborne severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus and environmental contamination in SARS outbreak units. J Infect Dis 191:1472–1477. doi:10.1086/429634.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

50. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Condition Engineers, Inc. (ASHRAE). 2017. Ventilation of health care facilities (ANSI/ASHRAE/ASHE standard 170-2017). American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Condition Engineers, Inc., Atlanta, GA.Google Scholar

51. Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology. 2016. HEPA and ULPA Filters (IEST-RP-CC001.6). Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology, Schaumburg, IL.Google Scholar

52. Goldsmith CS, Tatti KM, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Comer JA, Lee WW, Rota PA, Bankamp B, Bellini WJ, Zaki SR. 2004. Ultrastructural characterization of SARS coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis 10:320–326. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030913.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

53. Knowles H. 3 July 2019. Mold infections leave one dead and force closure of operating rooms at children’s hospital. Washington Post, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

54. So RCH, Ko J, Yuan YWY, Lam JJ, Louie L. 2004. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and sport: facts and fallacies. Sports Med 34:1023–1033. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434150-00002.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

55. Goldberg JL. 2017. Guideline implementation: hand hygiene. AORN J 105:203–212. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2016.12.010.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

56. Chaovavanich A, Wongsawat J, Dowell SF, Inthong Y, Sangsajja C, Sanguanwongse N, Martin MT, Limpakarnjanarat K, Sirirat L, Waicharoen S, Chittaganpitch M, Thawatsupha P, Auwanit W, Sawanpanyalert P, Melgaard B. 2004. Early containment of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS); experience from Bamrasnaradura Institute, Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 87:1182–1187.PubMedGoogle Scholar

57. Center for Devices, Radiological Health. 2020. N95 respirators and surgical masks (face masks). US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD.Google Scholar

58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Interim guidance for the use of masks to control seasonal influenza virus transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.Google Scholar

59. Ryu S, Gao H, Wong JY, Shiu EYC, Xiao J, Fong MW, Cowling BJ. 2020. Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings-international travel-related measures. Emerg Infect Dis doi:10.3201/eid2605.190993.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

60. Fong MW, Gao H, Wong JY, Xiao J, Shiu EYC, Ryu S, Cowling BJ. 2020. Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings-social distancing measures. Emerg Infect Dis doi:10.3201/eid2605.190995.CrossRefGoogle Scholar 61. Vandegrift R, Bateman AC, Siemens KN, Nguyen M, Wilson HE, Green JL, Van Den Wymelenberg KG, Hickey RJ. 2017. Cleanliness in context: reconciling hygiene with a modern microbial perspective. Microbiome 5:76. doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0294-2.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

62. Qian H, Zheng X. 2018. Ventilation control for airborne transmission of human exhaled bio-aerosols in buildings. J Thorac Dis 10:S2295–S2304. doi:10.21037/jtd.2018.01.24.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

63. Kim SW, Ramakrishnan MA, Raynor PC, Goyal SM. 2007. Effects of humidity and other factors on the generation and sampling of a coronavirus aerosol. Aerobiologia 23:239–248. doi:10.1007/s10453-007-9068-9.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

64. Casanova LM, Jeon S, Rutala WA, Weber DJ, Sobsey MD. 2010. Effects of air temperature and relative humidity on coronavirus survival on surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:2712–2717. doi:10.1128/AEM.02291-09.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

65. Chan KH, Malik Peiris JS, Lam SY, Poon LLM, Yuen KY, Seto WH. 2011. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv Virol 2011:734690. doi:10.1155/2011/734690.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

66. BioSpace. 11 February 2020. Condair study shows indoor humidification can reduce the transmission and risk of infection from coronavirus. BioSpace, Urbandale, IA.Google Scholar

67. Noti JD, Blachere FM, McMillen CM, Lindsley WG, Kashon ML, Slaughter DR, Beezhold DH. 2013. High humidity leads to loss of infectious influenza virus from simulated coughs. PLoS One 8:e57485. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057485.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

68. Marr LC, Tang JW, Van Mullekom J, Lakdawala SS. 2019. Mechanistic insights into the effect of humidity on airborne influenza virus survival, transmission and incidence. J R Soc Interface 16:20180298. doi:10.1098/rsif.2018.0298.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

69. Xie X, Li Y, Chwang ATY, Ho PL, Seto WH. 2007. How far droplets can move in indoor environments–revisiting the Wells evaporation-falling curve. Indoor Air 17:211–225. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00469.x.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

70. Yang W, Marr LC. 2012. Mechanisms by which ambient humidity may affect viruses in aerosols. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:6781–6788. doi:10.1128/AEM.01658-12.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

71. Memarzadeh F, Olmsted RN, Bartley JM. 2010. Applications of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation disinfection in health care facilities: effective adjunct, but not stand-alone technology. Am J Infect Control 38:S13–S24. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2010.04.208.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

72. Kudo E, Song E, Yockey LJ, Rakib T, Wong PW, Homer RJ, Iwasaki A. 2019. Low ambient humidity impairs barrier function and innate resistance against influenza infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:10905–10910. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902840116.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

73. Eccles R. 2002. An explanation for the seasonality of acute upper respiratory tract viral infections. Acta Otolaryngol 122:183–191. doi:10.1080/00016480252814207.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

74. Salah B, Dinh Xuan AT, Fouilladieu JL, Lockhart A, Regnard J. 1988. Nasal mucociliary transport in healthy subjects is slower when breathing dry air. Eur Respir J 1:852–855.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

75. Block SS. 1953. Humidity requirements for mold growth. Appl Microbiol 1:287–293. doi:10.1128/AEM.1.6.287-293.1953.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

76. Kembel SW, Jones E, Kline J, Northcutt D, Stenson J, Womack AM, Bohannan BJ, Brown GZ, Green JL. 2012. Architectural design influences the diversity and structure of the built environment microbiome. ISME J 6:1469–1479. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.211.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

77. Mhuireach GÁ, Brown GZ, Kline J, Manandhar D, Moriyama M, Northcutt D, Rivera I, Van Den Wymelenberg K. 2020. Lessons learned from implementing night ventilation of mass in a next-generation smart building. Energy Build 207:109547. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109547.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

78. Meadow JF, Altrichter AE, Kembel SW, Kline J, Mhuireach G, Moriyama M, Northcutt D, O’Connor TK, Womack AM, Brown GZ, Green JL, Bohannan BJM. 2014. Indoor airborne bacterial communities are influenced by ventilation, occupancy, and outdoor air source. Indoor Air 24:41–48. doi:10.1111/ina.12047.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

79. Howard-Reed C, Wallace LA, Ott WR. 2002. The effect of opening windows on air change rates in two homes. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 52:147–159. doi:10.1080/10473289.2002.10470775.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

80. Fahimipour AK, Hartmann EM, Siemens A, Kline J, Levin DA, Wilson H, Betancourt-Román CM, Brown GZ, Fretz M, Northcutt D, Siemens KN, Huttenhower C, Green JL, Van Den Wymelenberg K. 2018. Daylight exposure modulates bacterial communities associated with household dust. Microbiome 6:175. doi:10.1186/s40168-018-0559-4.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

81. Schuit M, Gardner S, Wood S, Bower K, Williams G, Freeburger D, Dabisch P. 2020. The influence of simulated sunlight on the inactivation of influenza virus in aerosols. J Infect Dis 221:372–378. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz582.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

82. Dijk D-J, Duffy JF, Silva EJ, Shanahan TL, Boivin DB, Czeisler CA. 2012. Amplitude reduction and phase shifts of melatonin, cortisol and other circadian rhythms after a gradual advance of sleep and light exposure in humans. PLoS One 7:e30037. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030037.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

83. Issa MH, Rankin JH, Attalla M, Christian AJ. 2011. Absenteeism, performance and occupant satisfaction with the indoor environment of green Toronto schools. Indoor Built Environ 20:511–523. doi:10.1177/1420326X11409114.CrossRefWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

84. Rutala WA, Weber DJ, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HIPAC). 2017. Guideline for disinfection and sterilization in healthcare facilities, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA.Google Scholar

85. Tseng C-C, Li C-S. 2007. Inactivation of viruses on surfaces by ultraviolet germicidal irradiation. J Occup Environ Hyg 4:400–405. doi:10.1080/15459620701329012.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

86. Lytle CD, Sagripanti J-L. 2005. Predicted inactivation of viruses of relevance to biodefense by solar radiation. J Virol 79:14244–14252. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.22.14244-14252.2005.Abstract/FREE Full TextGoogle Scholar

87. Bedell K, Buchaklian AH, Perlman S. 2016. Efficacy of an automated multiple emitter whole-room ultraviolet-C disinfection system against coronaviruses MHV and MERS-CoV. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37:598–599. doi:10.1017/ice.2015.348.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

88. Nardell EA, Bucher SJ, Brickner PW, Wang C, Vincent RL, Becan-McBride K, James MA, Michael M, Wright JD. 2008. Safety of upper-room ultraviolet germicidal air disinfection for room occupants: results from the Tuberculosis Ultraviolet Shelter Study. Public Health Rep 123:52–60. doi:10.1177/003335490812300108.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

89. Miller SL, Linnes J, Luongo J. 2013. Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation: future directions for air disinfection and building applications. Photochem Photobiol 89:777–781. doi:10.1111/php.12080.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

90. Welch D, Buonanno M, Grilj V, Shuryak I, Crickmore C, Bigelow AW, Randers-Pehrson G, Johnson GW, Brenner DJ. 2018. Far-UVC light: a new tool to control the spread of airborne-mediated microbial diseases. Sci Rep 8:2752. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21058-w.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

91. Buonanno M, Stanislauskas M, Ponnaiya B, Bigelow AW, Randers-Pehrson G, Xu Y, Shuryak I, Smilenov L, Owens DM, Brenner DJ. 2016. 207-nm UV light-a promising tool for safe low-cost reduction of surgical site infections. II: In-vivo safety studies. PLoS One 11:e0138418. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138418.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

92. Kembel SW, Meadow JF, O’Connor TK, Mhuireach G, Northcutt D, Kline J, Moriyama M, Brown GZ, Bohannan BJM, Green JL. 2014. Architectural design drives the biogeography of indoor bacterial communities. PLoS One 9:e87093. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087093.CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar

93. NIAID. 2020. Novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Flickr.Google Scholar

94. Yu IT, Li Y, Wong TW, Tam W, Chan AT, Lee JH, Leung DY, Ho T. 2004. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N Engl J Med 350:1731–1739. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa032867.CrossRefPubMedWeb of ScienceGoogle Scholar

95. Li Y, Duan S, Yu ITS, Wong TW. 2004. Multi-zone modeling of probable SARS virus transmission by airflow between flats in Block E, Amoy Gardens. Indoor Air 15:96–111. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00318.x.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

96. Liu Y, Ning Z, Chen Y, Guo M, Liu Y, Gali NK, Sun L, Duan Y, Cai J, Westerdahl D, Liu X, Ho K-F, Kan H, Fu Q, Lan K. 2020. Aerodynamic characteristics and RNA concentration of SARS-CoV-2 aerosol in Wuhan hospitals during COVID-19 outbreak. bioRxiv doi:10.1101/2020.03.08.982637.Google Scholar

Studie Ajit Ahlawat

Die Übertragung des schweren akuten respiratorischen Syndroms Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) durch die Luft wurde als potenzielle Pandemieherausforderung...

Einfluss der Luftfeuchte auf Mensch und Gesundheit

In der wissenschaftlichen Literatur werden unterschiedliche Empfehlungen für untere und obere Grenzwerte der relativen Luftfeuchte für Innenräume gen...

Auswirkungen von Umweltfaktoren auf COVID-19

Auswirkungen von Umweltfaktoren auf den Schweregrad und die Sterblichkeitsquote von COVID-19.

Saisonalität der respiratorischen viralen Infektionen

Der saisonale Zyklus von respiratorischen Virusinfektionen ist seit Tausenden von Jahren bekannt. Jahr für Jahr wird die Bevölkerung der gemäßigten K...

Luftfeuchtigkeit in Schulklassen

Influenza ist ein globales Problem und betrifft jährlich 5–10 % der Erwachsenen und 20–30 % der Kinder. Nicht-pharmazeutische Interventionen (NPIs) s...

Überlebensfähigkeit von Coronaviren

In dieser Studie wurden die Auswirkungen der Lufttemperatur und der relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit auf das Überleben von Coronaviren auf Oberflächen unte...

Optimale Raumluftfeuchte

Optimale Luftfeuchte in Räumen ist notwendig, um das Wohlbefinden des Menschen zu steigern, aber im Gegensatz zu den meisten anderen Schadstoffen in ...

Auswirkung auf das Sick-Building-Syndrom

Das Ziel dieser Studie war die wissenschaftliche Auseinandersetzung der Auswirkungen von Dampfluftbefeuchtung auf das Sick-Building-Syndroms (SBS) un...

Das saisonale Auftreten von Influenza Viren

Die im Winter beobachtete gesteigerte Sterblichkeit in gemäßigten Zonen wird zu großen Teilen der saisonalen Influenza zugeschrieben. Eine Reanalyse ...

Luftfeuchtigkeit in geschlossenen Räumen

Die Studie beschäftigt sich mit direkten und indirekten Auswirkungen der relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit auf die menschliche Gesundheit.